Dear Fabulous Female Founders,

A year ago, I had the extraordinary privilege of being at my stepfather Tommy’s side as he left this earth. He died of kidney failure at home, on a hospital bed in the living room, facing the backyard. He loved watching the wildlife back there: chipmunks, rabbits, birds, squirrels, lizards and the occasional bobcat that roam the bushes by the pool. His children, stepchildren, and grandchildren had all said their goodbyes in recent weeks. Nothing had been left unsaid. May we all be so lucky.

None of us succeed in business or life without love and support from the people around us. So today, I want to take you on a detour out of founder-land and into the messiness that is real life in my big, beautiful blended family.

Tommy Dean Thompson, born in Houston in 1936, lived a true rags-to-riches story, chronicled in his memoir, Exceeding My Own Expectations. A dyslexic farm boy and the first in his family to finish high school, he joined the Air Force Reserves and earned a mechanical engineering degree while working two jobs. As a contractor in President Kennedy’s space race, he contributed to over 30 projects before shifting to earthbound work—hospitals, schools, office buildings, and grain elevators—while indulging his passion for motorcycle and car racing. His first wife, Barbara, took care of the household and three children: Tommie, Cyndie, and Ronnie, who passed last month from the same kidney disorder as Tommy.

May Ronnie’s memory be a blessing to his family and all who knew him.

Love at First Sight

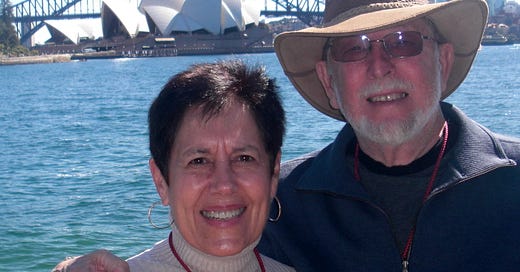

My mother was 45 when she went to a singles’ sailing event and spotted Tommy holding court, effortlessly in the know. Drawn in, she stayed by his side all evening, sparking a romance that lasted 38 years. In Tommy, she found a best friend and equal partner—someone who loved every part of her and fueled her own her creativity and curiosity. (More about my fabulous founder Mom here.)

They combed through garage sales, returning home with “treasures” they made uniquely their own—a dining table they topped with a swirling glass mosaic, a canvas they splattered in true Jackson Pollock fashion, and yoga balls they spray-painted into giant, floating marbles to keep ducks out of the pool.

They travelled the world, visiting more than 50 countries, reveling in the most distinctly different and unusual places, like the floating totora reed islands of Peru’s Lake Titicaca, the Yangtze River in China, and Inle Lake in Myanmar.

They brought together their seven children for epic Chrisnukkah gift exchanges they dubbed the Tacky Trinket Trade. We all got along just fine, thankfully, so they upped the ante by taking all of us plus spouses and kids, their own siblings, Tommy’s ex-wife Barbara, and my 92-year old grandfather (and his girlfriend) on a cruise, 32 people in all, a proud moment for two people who’d grown up poor.

One evening, Tommy and I were dancing in the lounge.

“Tommy,” I said, “that was awfully nice of you to bring along Barbara.”

He smiled slyly, explaining in his charming east Texas drawl that really, he did it for his kids, because Barbara would babysit their little ones.

“We both made mistakes,” he said, adding, “Thanks to her ditching me, I got to meet your mother.”

Skeptic Turned Supporter

Tommy’s initial reaction to my chosen career was skepticism. (In this, he wasn’t alone.) “Money, it’s all about money,” he’d say when I preached about energy conservation during my first job out of grad school. “Show me how your fancy light bulbs are going to save money.”

I’d sputter moralistically about saving the earth one lightbulb at a time. He’d retort, “you don’t know that” (which I really didn’t) or “prove it” (which I couldn’t.)

When I started working for the City of Portland’s Bicycle Program, he poked, with cheerful certainty, “Mia, people are not going to ride bikes to work.”

Now, here’s where it got interesting, for by then, I actually knew my stuff. I’d present hard data along with pictures from my travels to bike-friendly European cities, and he’d smile and acknowledge that maybe I had a point or two.

As I made inroads in Portland and later, dozens of cities through my consulting firm, I’d share stories with him, curled up on their couch on visits to Texas. He loved his work, for a construction company called Dynaten, where he led business development. There, our worlds resonated as we each hustled to win work in our respective fields.

I’d go on about my latest marketing drama—the competitor who used to work for the client, the behind-the-scenes manipulation, the price undercut, the nightmarish government bureaucracy—and he’d laugh and state with absolute certainty, “but you love it, you just love it.” Because he loved it and felt (as he told me many times) that the game of business was second best to sex.

“Most of his activities and achievement related to the fact that he was an adrenaline junky. That’s why he raced lots of vehicles, and procrastinated.

His best ideas came as the deadlines loomed.” ~Mom

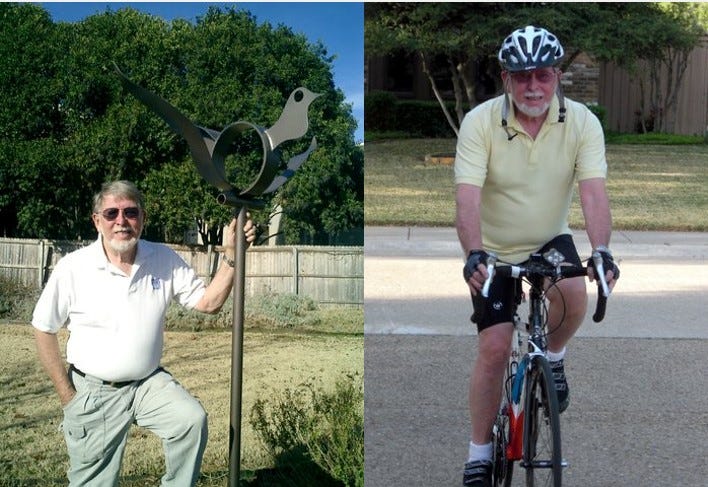

One day, I arrived and had barely finished wheeling my suitcase to the guest room when he grabbed my arm and led me to his “toy box,” a corrugated tin shed stuck to the side of the house where he played with latest hobby, be it toy “yachts” (which he raced on their subdivision pond), metalwork, or ceramics.

“Check this out,” he crowed, pointing to a three-wheeled recumbent bike festooned with a bright orange flag. “I love it!”

Within short order, he upgraded to a road bike and lost 30 pounds. No, he didn’t ride his bike to work—thoroughly impractical in their location—but he did fall in love with bicycling as a form of exercise and recreation. Just as good, in my opinion.

Last Days

When I arrived at their house in Carrollton, TX for Tommy’s last days, he was still somewhat lucid. A modest, tidy, one-story home in a quiet planned community, their walls and shelves explode with memory and creativity: glass sculptures from Murano, masks from Africa, and three-feet-tall wooden sculptures of jazz musicians playing a sax and stand-up bass made by Tommy himself.

Hospice nurses were coming daily, but mostly it was just my mom taking care of him, as she’d done for the past few years as his health declined. A hereditary kidney disorder should have taken him down decades earlier, but they’d kept it at bay with rigorous attention to diet and exercise, plus a healthy dose of luck. At 88, his luck had run out.

Above all else, Mom and Tommy wanted him to die at home, in sync with passionate feelings about end-of-life control and death with dignity. They constantly reminded all their kids of their wishes and made sure we had copies of their advance directives and DNRs. Their resolve had only strengthened as elderly friends and relatives underwent heroic—in their minds, torturous—treatments that only served to prolong the inevitable, at tremendous financial and emotional cost. They’d say, “And for what? A few more months? When they’ve lived a good, long life? Why can’t people accept that death is a part of life?”

As soon as I reached Tommy’s bedside, he smiled and said, “Hey kid, it’s good to see you.’”

“It’s good to see you too, Tommy.”

“There’s something wrong here,” he said, gesturing at his emaciated body. “I just have to figure out how to fix it.”

“Aw Tommy,” I said. “You’ve fixed a ton of things, but I don’t think you can fix this one.”

“You know, kid, I think you’re right. I think you’re right. But it’s ok. I’m ready.” He squeezed my hand, and I believed him.

Over the next few days, rambling conversations turned to mumbling, then silence as his organs shut down and he sank into unconsciousness, unmedicated, breathing in fresh warm air and gentle jazz melodies. Mom and I tended to his pillow and blankets, dribbled water in his mouth, and consulted end-of-life checklists. Mom, a financial planner, left nothing to chance, from the distribution of his estate to the donation of his body to science, for she’d seen way too many families rip themselves apart squabbling over money, mementos, and beliefs.

Sometimes, his arms would jerk straight up, his hands turning imaginary motorcycle handles or painting or waving like a sea anemone, and I’d reach over and gently pull them down and stroke his hands until he settled down. Sometimes, his chest would heave or rise, bits and pieces of his soul floating up and into the universe, or so I imagined. He never seemed in pain.

I stayed in touch with my siblings and step-siblings, holding the phone up to his ear and transmitting their messages of love.

The morning of his death, a nurse came by and said that it could still be days or even weeks. Then, Mom went to take care of something in her office just a few steps away. I stayed by his side, my hands on his, as he took one deep breath, then another.

Then: no more.

Here’s what I wonder: did Tommy perceive a subtle shift in the room’s energy that allowed him to let go—I’ve heard stories like that before—or was the timing mere coincidence? Whatever the case, I felt myself to be the recipient of a rare and precious gift, alongside the others he’d given me and my family, especially loving our mother so deeply for so long.

His death was as beautiful as his long, interesting life. May we all be so blessed.

~Mia

💐Epitaph💐

by Merrit Malloy

When I die

Give what’s left of me away

To children

And old men that wait to die.

And if you need to cry,

Cry for your brother

Walking the street beside you.

And when you need me,

Put your arms

Around anyone

And give them

What you need to give to me.

I want to leave you something,

Something better

Than words

Or sounds.

Look for me

In the people I’ve known

Or loved,

And if you cannot give me away,

At least let me live on in your eyes

And not on your mind.

You can love me most

By letting

Hands touch hands,

By letting

Bodies touch bodies,

And by letting go

Of children

That need to be free.

Love doesn’t die,

People do.

So, when all that’s left of me

Is love,

Give me away.

❤️

Beautiful tribute thank you! ❤️