Dear Fabulous Female Founders,

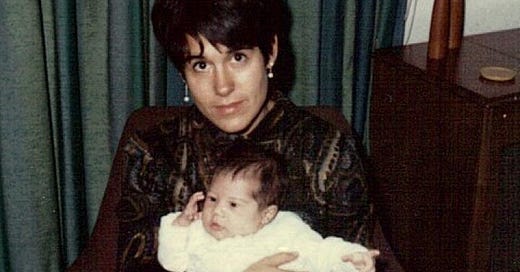

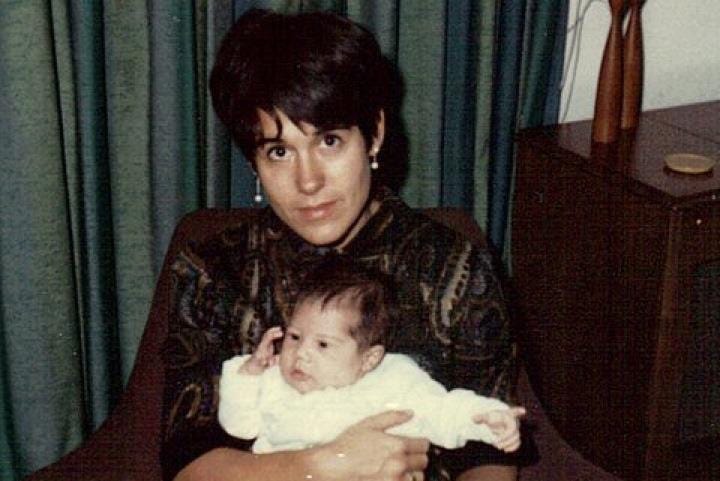

If I were to pick a single word to define my family ethos, it would be ‘independence,’ not just a word but a parenting philosophy: children should be highly capable and self-determined. By 16-months, my mother (Joyce, née Charlotte) expected me to pitch in with my two-month old brother Glenn by feeding him a bottle, which she stored within reach on the fridge’s lowest shelf. She sent me to a French Montessori pre-school because of their compatible philosophy: if you give young children freedom to choose and act freely within a controlled environment, they will become capable adults. By the age of five, I had absorbed three languages: English, French (my parents both were born and raised in Montréal), and the language of self-determination.

I believe that my mother’s philosophical leanings emerged from childhood trauma, the loss of her mother at age seven. Until age five, money was tight but life was pleasant. Grandfather Leon (Zayda) owned a scrapyard; his wife Florence, took care of their home and daughters Joyce and Hannah.

One day, Florence came inside from trip to the lake, her arms itchy, bumpy, and blotchy with poison ivy. She took a long hot bath, spreading the poison all over her body; within hours, the misery was so great that an ambulance was called. Florence was carried away on a stretcher and never came home.

In today’s world, death from a poison ivy reaction would be inconceivable. In the 1940s, perhaps not, not if the rash becomes severely infected and the patient is treated with a relatively new drug–penicillin–to which they are allergic. But no one really knows what happened; Mom remembers visiting a mental hospital, her father being gone a lot, and him taking them to a graveyard and pointing to a headstone he claimed was their mother. No explanatory records were ever located.

For the two years in between her mother’s departure and death, my mother felt responsible for her little sister, and for good reason: she was often in charge, taking care of her for hours at a time when a neighbor or relative wasn’t available. One day, outside their apartment, playing with neighborhood kids, unsupervised by adults, my mother ordered Hannah to come home. Back and forth went the dialogue between motherly six-year-old Joyce and defiant three-year-old Hannah, who laid down in the street and threw an epic tantrum just as a car was ambling along. Hannah’s broken leg healed quickly, much more so than my mother’s emotional wounds.

When their mother died, Hannah went to live with protective Aunt Dinah, my mother to laid-back Aunt Adele. A time later, their father returned with a woman named Sarah, also known as Sookie, who, in short order, had Harold then Ruth. Even as my mother became fond of her younger half-siblings, she never lost sight of what she had gained during this period of loss and instability: a ferocious sense of self-sufficiency and an imperative–depend only on yourself–that she would carry forward into her adult life and infuse into her children.

***

My mother attended McGill University and earned a degree in occupational therapy. She worked in Switzerland, then met my father at a ski resort near Montreal. They moved to a tiny apartment in New York, where Dad earned an MBA at Columbia and my mother worked as an occupational therapist at the Institute for the Crippled and Disabled. In the meantime, their hometown underwent massive upheaval in the form of a nativist uprising; new laws declared French the official language, mandated French-only education, and required French to be used exclusively on public signage. Most English companies decided to leave, freezing out my parents and leading to them seek American employment and citizenship, which led to our move to Maplewood, New Jersey, where a split-level three-bedroom starter home with a backyard, basement, and bomb shelter could be acquired for the princely sum of $35,000.

My three brothers were born in rapid succession: Glenn, 14 months after me; Bruce, 16 months later; and Russell, just 13 months after Bruce. Four kids in three and a half years! Why not two or three kids? Why not spaced out more? Because Mom had studied birth order and concluded that two is too few–you don’t get the group dynamic–and three creates a middle child who inevitably suffers. Further, the closer in age, the easier to manage, or so the research showed.

Perhaps she would have changed her plans when Glenn’s colic persisted well past the first few months, but it was too late, she was already pregnant with Bruce. Enter sweet, loving, jowly Mrs. Panitch, who had the patience to rock bawling Glenn all day long and who stayed with us as Bruce and then Russell entered the picture.

Relieved to have a few hours of daily adult time, Mom found a job in vocational rehabilitation in Newark, while Dad began his career in electronics at a small company that gave him the opportunity to learn and grow and invest in his own infantile software division. One day, he arrived at padlocked gates; the parent company had gone belly up. A short while later, a Dallas, TX-based company purchased the company’s assets out of bankruptcy, offering Dad a job and Mom a much desired warmer climate.

***

That first summer in Dallas, we crammed into a tiny two-bedroom apartment while Dad sold electronic equipment and Mom bought an air-conditioned car, house-hunted, enrolled us in school, and applied for jobs. In their early 30s, strangers in a strange land with four small children, no family or friends, little cash and mounting bills, and somehow, they muddled through it.

Mom’s job was her savior. Called Avodah–Hebrew for ‘work’–it picked up where she had left off in New Jersey, providing jobs and vocational counseling for physically and emotionally disabled adults and seniors, a program she founded within a social service agency.

That brings up a question I recently got from a friend whose been working for five years on a soon-to-be funded mental health initiative. She asked, “Does that make me a founder, even though it’s a non-profit/government program?” The answer: heck yes! If you create a business, non-profit organization, or a program like my mom’s, whether alone or with collaborators, whether with ambitions to scale and grow or stay tight and small, you get to call yourself a founder or cofounder.

Back to my Mom. Sick days, holidays, and weekends, my brothers and I would join her at Avodah, either reading quietly under her desk or working on the assembly line. We pasted plastic American flags onto little sticks for people to wave at parades. We stuck colorful stickers onto bicycle wheel reflectors that made a rainbow when you pedaled. We slid Mary Kay mascara tubes into finger-sized rectangular boxes, then stacked them in bigger boxes. Mom did everything, from negotiating contracts to driving the bus to figuring out assembly line efficiency. Factoring in the 60-hour work week, she earned half of minimum wage but gained insight: since she was actually running a company, maybe she should go back to school and get an MBA herself? At age 40, she enrolled at Southern Methodist University, where she earned her degree in a year, which she followed up with a top ten statewide score on the exam to become a certified public accountant (CPA.) Her corporate career included stints at major companies selling jewelry, toys, and travel. Finally, she became (and still is) an excellent and sought-after financial advisor, universally loved and appreciated by her children, step-children, grandchildren, siblings, friends, clients, and late-husband Tommy, may he rest in peace.

Happy Mother’s Day Mom! Thank you for the toolkit of independence. Thank you for the instincts to step up when needed, to sense the needs around me, to find self-worth in responsibility, and to be self-reliant. Thank you for the work ethic you instilled in me. Thank you for being you.

And Happy Mother’s Day to all you fabulous female founders simultaneously raising children and companies or organizations. I know that sometimes it feels like an impossible equation, that you can’t give both your kids and companies everything you want to give. That’s ok. Give what you can when you can, and give yourself credit for all that you are doing, all that you are, all that you’ve created. Our purpose in part as moms is not to do everything for our kids but to prepare them to launch as adults. The lessons my Mom imparted on me are valuable for us all.

Wishing you all the best,

-FFF